George Lagarias, chief economist at Mazars, comments on the future of Quantitative Easing.

It may be difficult to remember, but in the midst of the global financial crisis and long after, Quantitative Easing (QE) wasn’t really trusted by markets. For the next five to seven years, almost until 2015, most money managers did not trust the bull market and remained underweight risk. They paid with underperformance and the rise of passives. Then, we began to wonder what could ever stop the QE juggernaut. The answer was always simple: inflation.

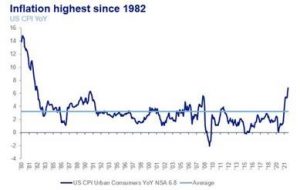

Last week saw US inflation hit a 40-year record of 6.8%. The fine print says that the bulk of the price rises focuses on energy prices and cars/trucks. And also, that it is supply, not demand-driven, which means it would respond very differently to interest rate hikes. However, once a number like that hits the headlines, details are forgotten and things happen quickly.

It is difficult to find a participant in today’s market who remembers what this kind of price pressure even feels like. Last time inflation was running this hot, the Cold War was raging, personal computers had not been invented, ‘Chariots of Fire’ was named the best movie of the year and Ben Cross was the hottest name in acting. Meanwhile, an unlikely Hollywood actor named Ronald Reagan had newly occupied the White House. Interestingly enough, however, the present incumbent in the Oval Office, Joe Biden, was already a 10-year Senator from Delaware. His memory of how inflation brought down his party’s President, Jimmy Carter, should be vivid as he sees his own approval ratings slide for the same reason.

In the last twelve years, monetary accommodation ballooned and central bank assets for the US and the EU rose nearly eight times. All they achieved was a meagre 1.5% inflation. Policy leaders fretted about deflation and tortured their intellects about how to normalise the yield curve again and turn money lending into a profitable operation once more. They talked rates up; they tried to stoke inflation expectations but to no avail. The yield curve remained flat as a pancake. It took a global pandemic and the biggest post-war supply chain shock to see inflation.

Inflation might not necessarily always be a monetary problem. It is, however, always and everywhere a political one.

Since 2008, the US central bank has exercised a dominating amount of control over the prices of all assets across the risk spectrum. It was not just its ability to throw trillions into financial markets at the push of a button. It was the threat that this posed to short-sellers. No one wanted to be caught with short positions at any time when the US central bank would decide to start printing. So, they were long.