The IMF has predicted India will grow 9.5% in the year to March 2022 – the fastest pace of all major economies. The updated estimate was announced following record economic growth in India in the second quarter for the world’s sixth-largest economy. This, among other encouraging data points demonstrate the genuine underlying investment case of a country hit hard by Covid19, say Andrew Draycott and Abhinav Mehra from Coupland Cardiff Asset Management LLP.

A 20.1% surge in India’s GDP growth was reported just days after Barclays announced a $400m investment in the country – it’s largest capital injection over here in three decades. The bank’s bosses have said they were hoping to take advantage of economic momentum in Asia’s third-largest economy, which is something we can get on board with.

It’s important to note the record GDP figures rebounded from a very low base as the economy contracted 24.4% over the second quarter in 2020. But the social and economic damage wrought by the pandemic, particularly in the second wave, never diminished our conviction in the Indian investment opportunity.

India’s investment profile

At the end of the last year, with the Pfizer vaccine announcement and Covid-19 cases seemingly benign, we had started to see an acceleration in economic activity across many verticals. But with the onset and ferocity of the second wave, it’s unsurprising that earnings for a lot of the companies in our portfolio were put on pause.

This is not solely covid-related though. Even in the last 10 years prior to the pandemic, India had been going through a corporate recession with credit growth slowing consistently and reaching mid-single digits, a far cry from the 1.5x nominal GDP growth that one would expect in a growing underpenetrated developing economy.

Part of the reason behind this was the domination of the banking sector by public banks, with the ensuing corruption of managers lending to friends. Non-performing loans had peaked at >11% in 2018, which meant strict rules had to be brought in especially on public sector banks, with many put under PCA (Prompt Corrective Action) – restricting their ability to lend. This had the impact of slowing everything down, essentially removing the oil from the gears of the economy.

Prior to the second wave, the pent-up demand created by the first wave, plus years of restricted lending, seemed to be surging to the surface. We were seeing early signs of a construction boom and capex revival for manufacturing. The Sino-American difficulties with trade were another prospective tailwind in India’s favour.

A blueprint for tackling challenges

Thankfully, when the second wave struck in March 2021, people had the blueprint from the first lockdown. Foreign Institutional Investors withdrew capital as expected, causing a market correction of around 10%.

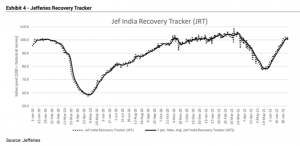

From an investment standpoint alone, however, the second wave was not as significant as the first. This is demonstrated by the Jefferies Recovery Tracker.

In late February 2020, at the start of the first wave, the index was at 100 then falling to around 60 at its lowest point in early May. By November, it had fully recovered, taking over six months to reach its pre-pandemic level.

In comparison, in March 2021, when the second wave began, the index slumped from 100 to around 80 and was already back to 100 by July. It fell only half as far and took only half the time to recover. The market reaction was almost identical in terms of shape but shallower and shorter.

According to the WHO, we are now potentially at the stage where Covid-19 is reaching endemic, rather than epidemic levels in the Indian population – so the hope is, the worst is over.

Concentrated access with conviction

Our portfolio is specifically designed to take advantage of domestic growth in India. At inception we eliminated any holdings that were externally facing exporters, which makes up a large portion of our benchmark (the MSCI India Index) with sectors like IT, pharma, oil & gas refining, speciality chemicals and global commodities.

This means the fund was acutely positioned to be punished by lockdowns, but on the flipside, we believe it is now acutely positioned for the expected boom in India’s domestic economy.

The past 12 months have been painful, and yet we still returned 47.8% over this period (as at the end of July 2021). From an investor allocation perspective, they are likely to have emerging market (EM) exposure that holds the types of Indian companies that we do not (exporters). If the average investor has only 10% of their portfolio in EM, and only an average of 13% of most EM funds is invested in India, they are likely to only have around 1.3% invested in India.

Within that, the majority will typically be invested in exporters rather than companies exposed to the domestic consumption story. While growth estimates in India for the year have been cut from 12-13% to about 9.5% in 2021, we still see it as on track to be one of the fastest growing economies over the next few years.

In our view, to make the most of this opportunity, investors should reassess whether a broad emerging markets fund is the best place to be.