Strategist Sahil Mahtani explains why the mantra of investing in so-called ‘hard assets’ during inflationary environments has a number of pitfalls, and why an active approach is more likely to benefit portfolios.

In the US, inflation averaged 1.7% per year during the 2010s, compared to 2.5% during the prior decade. Low inflation and accommodative monetary policy underpinned an unusually long bull market for stocks, falling yields for bonds and a strong negative correlation between the two asset classes. In that environment, stock and bond portfolios generated strong positive real returns.

Yet inflation over the coming decade is expected to be closer to the experience of the 2000s than the 2010s, and perhaps higher. While downside risks remain, the more dominant drivers are aggressive monetary and fiscal easing and high energy prices, which were rising even before the Ukraine conflict. This is compounded by longer term factors like increased investment spending from green investment, stronger working age population growth in the US, not to mention the triumph of political populism in several countries, which has encouraged higher public spending, higher defence spending, and more capital-intensive supply chains. In other words, the post-pandemic world could herald a different inflation regime.

The ‘hard asset’ mantra

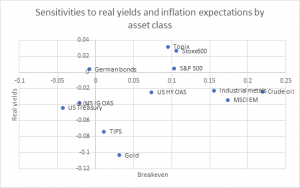

Navigating such an environment is not easy. Certain assets have historically done better or worse under different macro regimes. For example, breakevens data –a measure of investors’ inflation expectations – over the last two decades suggests that in an environment where prices are set to rise, investors should be overweight oil, emerging markets, industrial metals, and equities while being underweight treasuries. Hence the mantra of buying real, tangible assets, also known as ‘hard assets’, rather than financial assets.

Source: Ninety One (Data since 30 January 1999)

But it is not as simple as that.

The conceptual distinction between real or hard assets and financial assets is messy. Some financial assets undoubtedly have claims on real assets. Equities, for instance, may own tangible, physical assets. Similarly, a physical gold ETF, or a royalty company, is a claim on underlying physical assets or cash flows resulting from the sale of those physical assets. Meanwhile, financial assets like inflation-protected securities can protect wealth in real terms despite no physical asset backing. The distinction between hard and financial assets is probably a legacy of an economic world tethered to a gold standard. In today’s heavily financialised world, real assets and financial assets are fundamentally intertwined and it makes little sense to define assets by whether they have physical backing or not.

Stick to the basics

Investors should be sceptical of historical analogies. We have a very limited dataset of asset class returns at our disposal–typically a single-digit number of decades worth of data. In particular, inflation-linked bonds that are used to indicate real rates have only existed since 1981 (UK), 1997 (the US) and 2006 (Germany)–none of those encompassing major inflationary episodes. Meanwhile, expectations have been anchored since the 1990s.

Crucially, it matters what is inflating. In the 1970s inflation episode, high money supply growth interacted with scarce oil resources, exacerbated by wage growth from union intransigence in some countries, lifting inflation expectations in the public. Today, the drivers of inflation appear to be tilted more towards supply chain disruptions, natural gas more so than oil, and wage growth from shrinking labour force participation. It may also be the case that we are not in a world of ever rising inflation but one of higher inflation volatility. In other words, inflation exhibits large or persistent upside or downside inflation surprises.

A dubious distinction

Some parts of the conventional answer for portfolios make complete sense. Sovereign bonds in the US and Europe are highly priced, generate fixed nominal returns, and may not hold their value in an inflationary environment given current prices. However, sovereign bonds in Asia could be attractive given lower inflation and higher starting yields there. Currencies, either commodity price beneficiaries or creditor nation currencies, also represent a neglected opportunity set in such circumstances, offering both diversification and returns.

But other parts of the ‘real asset’ vs ‘financial asset’ distinction remain dubious. For instance, real estate investment trusts do poorly in an environment of rising inflation breakevens. Given exceptionally high starting valuations globally, not to mention fluctuations in the geographical location of commercial activity driven by the pandemic, it is not clear these should be a cornerstone of inflation protected portfolios.

Bottom-up selection is crucial

In equities, the key is arguably unchanged: hold companies that have the ability to increase prices easily, even with flat volumes and when capacity is not fully utilised, without fear of market loss, and those that have an ability to accommodate large increases in business with only small additional capital. Some software companies, which investors tend to see as not benefiting from a higher inflation, higher rate world, actually fit these characteristics more than some of the ‘value’ companies that investors conventionally see as benefitting from inflation protection.

If we are entering a world of above-target inflation for several years to come, investors should ditch the easy answers. Conventional 60-40 type portfolios are likely to struggle, especially those that rely on US and European bonds. Some real assets like real estate and particular commodities may not work. Investors should reflect about what specifically is driving the inflationary process, and invest in equities that have pricing power but are not at frothy valuations.

Finally, in a world of higher inflation volatility and high starting asset valuations, central banks are going to remain a key driver of liquidity and therefore asset returns in the years ahead. Their new doctrine means they will put the foot on the accelerator for longer when they are missing their targets but also put their foot on the brake quicker when they meet them. This implies that static asset allocation may become increasingly suboptimal and dynamic asset allocation will be more necessary.