Last quarter saw the passing of the One Big Beautiful Bill; Trump’s tax cutting bonanza that was met with relative calm in markets, even though Elon Musk, once an ally, blasted it as a “disgusting abomination.”

Musk was attempting to reduce the budget deficit – the measure by which a government spends more than in earns in taxes – by cutting government spending. He was therefore strongly against this bill that undermined his work. Nevertheless, Trump passed the bill into law by the narrowest of margins and now the budget deficit is expected to stay well over -6% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the deepest deficit outside of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the pandemic since at least the 1970s.

It’s now the UK’s turn to unleash a big fiscal event in the upcoming Autumn Budget, scheduled to take place on the 26 November. We are in a similar fiscal situation to the US in that the budget deficit is also the widest it’s been outside the GFC and the pandemic at c. -5.5%. However, it is highly unlikely that tax cuts are coming in the UK. On the contrary, another “black hole” is said to be needing filled, which is political talk to say taxes will rise.

Hence there are parallels to the last Budget in 2024. And given the market reaction then, the upcoming Budget will be influential on UK assets in the coming quarter. UK government bond yields, as an example, are the highest across the developed nations of Europe and the US with the 10-year gilt having risen over 40 basis points since last year’s Budget.

Elsewhere, markets have generally remained buoyant this quarter. Emerging markets kept pace with a resurgent S&P 500 as AI-related momentum resumed. Yet Japanese equities outperformed both markets, underscoring once again that opportunities for attractive investment returns extend well beyond the United States.

A quick recap on what happened after last year’s Budget. On 30 October 2024, Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced £40 billion in tax rises, making it the biggest budgetary tax hike since 1993. An increase in employer National Insurance Contributions was expected to raise about £25 billion per year of this £40 billion. Therefore, business was expected to shoulder this significant tax burden.

According to the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), their Business Confidence Monitor for Q2 2025 shows that confidence fell further into negative territory, with tax burden challenges being close to a record high.

The unemployment rate has also risen since last year’s Budget, from 4.3% to 4.7%. Although a tax on business may have filled some of the quoted black hole in public finances, the evidence suggests that it has not supported the growth side of the economic equation. Indeed, GDP is expected to increase by 1.2% in 2025, which is much lower than the 2% that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast at the time of the budget. The challenge for the chancellor is that an economy that is demonstrating sluggish growth ultimately results in lower overall tax receipts.

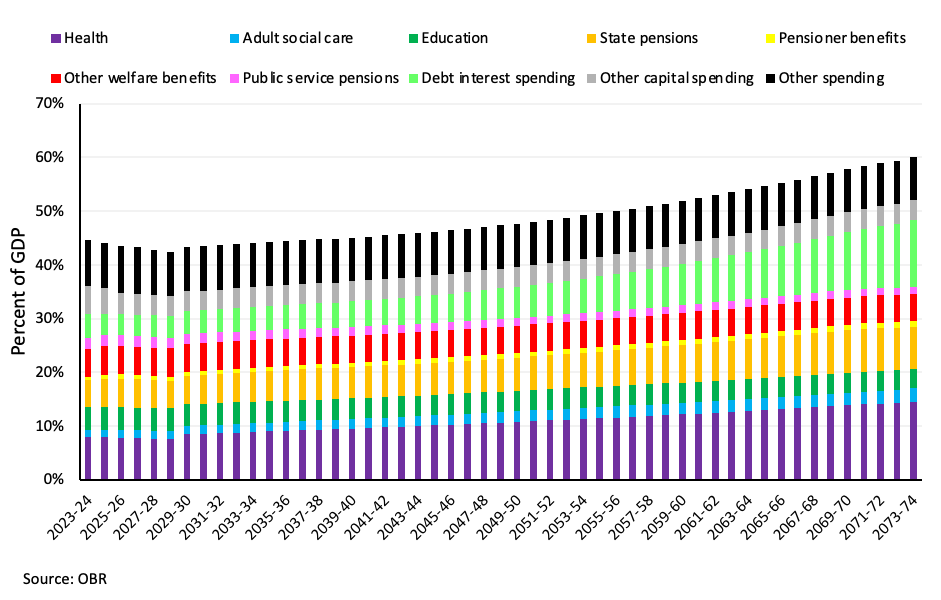

Rather than talk of black holes, Figure 1 shows why the Chancellor thought it necessary to raise taxes. Government revenue generation as a percentage of GDP is expected to flatline over the next five decades. Thinking simplistically, if a government needs more revenue, it should raise taxes, and this is what the UK Government did last year to the sum of £40 billion.

Figure 1: Forecasts of UK public finances as a percentage of GDP in terms of revenue generated from taxes and government spending.

But what Figure 1 also shows is that the UK doesn’t have so much of a revenue problem. Rather, it has a very big spending problem, as we can see from the completely unsustainable rise in forecasted spending as a proportion of economic output.

The question for this quarter is clear. What can the government do in the upcoming Budget to fix this?

The Autumn Budget in 2025

Can the Government raise taxes again? It is certainly the expectation if we believe the many headlines. Let’s look at the four main revenue drivers, making up about two-thirds of tax receipts.

Income tax – The largest revenue generator, but the Labour manifesto promised not to raise taxes on “working people,” so this would be politically damaging. Raising income tax would also reduce the potential for discretionary spending in the economy and would therefore reduce growth expectations.

Corporation tax – Politically risky given the huge increase in employer National Insurance Contributions last year. It would also slow business investment further, and signs are that hiring is already slowing.

VAT – Another potential hit to discretionary spending if this tax is raised. It would also be inflationary and therefore risk the Bank of England holding off on further interest rate cuts.

Employees’ National Insurance Contributions – This would be another way to reduce the net amount received in payslips and in turn reduce demand. It would also be interpreted as a tax on working people.

Admittedly, the above is a broad-brush approach to tax policy, but it highlights the challenge of pulling the tax lever even further after last year’s hike. Other policies, such as wealth taxes, are also being proposed to solve the black hole. The problem with a wealth tax is that it almost never works because high-net-worth individuals are highly mobile; hence it results in capital flight and reduced investment. Switzerland is one example whereby a wealth tax has been a relative success, but this is largely due to other taxes, such as a capital gains tax, not being imposed. As such, the UK already has forms of a wealth tax by applying tax to capital gains.

It can be useful to apply the Laffer curve when discussing tax policy. It illustrates that tax revenue first rises but then falls as the average tax rate increases. Simplifying, if the overall tax rate is 0% then your government revenue will of course be zero. However, increasing this tax rate does not lead to a linearly increasing rate of tax revenue. For example, in the most extreme case where the tax rate is 100%, there would be zero incentive for people to work, or business to invest, and your economy shuts down.

There is an optimal point in between a tax rate of zero and 100% whereby tax revenue is maximised without stalling the economy. Judging by the past 12 months since the Budget, the UK is likely already past this optimal point. As it stands, the tax burden is set to be the highest since records began, stretching back to the end of World War II.

Consequently, increasing tax will be hard to do on the 26 November. Yet we are likely to see taxes rise as the chancellor has set two key fiscal rules:

- Day-to-day government spending must be met by tax revenues (no borrowing for regular operating costs).

- Public debt must be falling as a share of GDP by 2029-30.

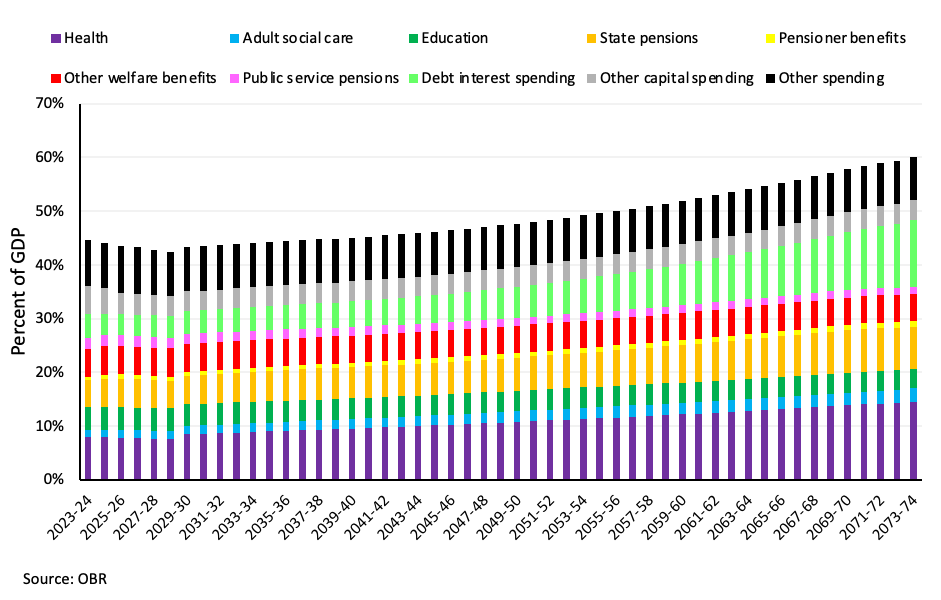

We can interpret the first rule by saying the chancellor must raise taxes to pay for more spending. In turn, debt issuance will be reduced as more tax revenue flows into the Treasury, and this will achieve rule 2. This ignores the Laffer curve by assuming raising taxes commensurately increases revenue without any impact on economic growth. But as we saw in Figure 1, the bigger issue is one of spending, rather than revenue generation. Looking at this further, Figure 2 shows the breakdown of headline government spending as a percentage of GDP. The three biggest areas of increased spending across the dataset are: debt interest, health, and state pensions.

Figure 2: Forecasts for the components of government spending as a percentage of GDP.

Rising debt interest costs is a symptom of a government increasingly spending more than it generates in tax revenue. Issuing more debt to cover the gap comes at a cost of higher interest costs, as we can see in the above chart.

Health is a close second place for increased spending as a proportion of the economy. Health being the NHS. If we started with a blank piece of paper, it is highly doubtful that the NHS would be created in the form it is in today. We cannot, of course, start afresh with the NHS, but it is unlikely that increasing spending in the way that Figure 2 shows is the answer. Already the budget for 2025/26 is about £200 billion, up from £121 billion in 2019/20. As a policy, we need to improve productivity and value for money in the NHS. The process to do this is far trickier, but simply increasing spending as a proportion of the economy does not look sustainable.

The third biggest increase in spending as a percentage of GDP is the state pension. Current policy is for the ‘triple lock’ to increase state pensions by the greater of 2.5%, the previous September’s inflation rate, or the increase in average earnings. Given that private earnings growth rose 4.7% year-over-year to July, the state pension will now likely rise by this amount next April.

Questions have been raised on the sustainability of the triple lock policy. Even Sir Steve Webb, the minister who launched the system, has noted that it cannot continue in perpetuity. But further commentators have noted that the state pension may not be sustainable regardless of the triple lock, and that we must focus on private means of funding retirement in generations to come. Means-testing the state pension has also been proposed, and Figure 2 suggests that this might be necessary.

The political problem to the above is that these radical changes do not win votes. We saw that reforms to the welfare system failed in parliament only months ago, noting that adult social care and welfare benefits are not an insignificant amount of government spending and are expected to increase as a proportion of our economy (Figure 2).

Hence this coming Budget is largely expected to be a repeat of what happened last year. We will probably see tweaks to taxes, such as freezing income tax thresholds again and applying National Insurance on rental income, but it is speculation at this stage.

It is highly unlikely that we see the radical reforms that are required. Until we do, the UK will maintain its spending problem and simply hope that it can grow its way out of it.

Looking Further Afield

UK markets usually only make up a small fraction of the overall asset allocation in a diversified portfolio. However, for all the political and fiscal challenges, all is not lost when it comes to UK assets. For instance, government bonds do offer healthy yields above expected inflation having already priced in a lot of the fiscal trouble outlined above.

The FTSE 100, an index of largely international companies, has also risen almost 16% including dividends so far this year, above the S&P 500 at time of writing in both sterling and local currency terms. UK stocks are also very cheap and both private equity groups and the companies themselves are taking advantage by buying up the shares. Almost two-thirds of FTSE 100 companies are buying back their shares as they are perceived as cheap, while the percentage of AIM 100 companies doing the same is at a near-record stretching back to the beginning of this century.

As noted, Japanese equities have performed strongly in the third quarter, beating the likes of the FTSE 100, S&P 500 and the broader emerging markets index. In recent times, the Japanese regulator and the Tokyo Stock Exchange have pushed companies to reform and prioritise shareholder returns. Evidence suggests it is working as companies increase share buybacks and dividends, and corporate governance standards are improving as management are engaging with shareholders.

On the macro front, it appears that the long period of deflation is over, and wage growth has accelerated. There are still risks, not least trade tensions with the US given Japan’s export-driven markets and related currency strengthening as the dollar weakens. Structurally though, Japan’s markets look appealing for the longer term.

Finally, on the point of a weaker dollar, it looks all but guaranteed that the Federal Reserve will begin its second round of interest rate cuts, starting in September. Leaving the political and economic ramifications of this aside, it should result in further weakness in the dollar. Given the world’s export markets mostly function on the dollar, and emerging markets have a significant amount of dollar-denominated debt, a weakening of this currency is usually supportive for this dispersed region. Emerging markets also benefit from a more favourable demographic and generally higher economic growth rates.

Beyond Japan, the Emerging Markets Index outperformed its developed market peers in the third quarter. There is no guarantee this will play out for the rest of 2025, but in a diversified portfolio, emerging markets are keeping pace again and generating returns for investors. It has been quite some time since this was the case.